Sanderling

General Description

The Sanderling is a small, light-colored sandpiper with a straight, black bill and black legs. The male and female look similar. In breeding plumage, it has a rufous head and neck and a rufous wash that extends onto its back. In non-breeding plumage, the adult is white underneath and very pale gray above while the juveniles are white underneath with a dark and light mottled top. Late-molters, Sanderlings don't reach their breeding plumage until late May. This is the only sandpiper that lacks a hind toe, which allows it to be a strong runner.

Habitat

Sanderlings breed farther north than any of the shorebirds found in Washington, nesting in dry, rocky tundra on the land closest to the North Pole. In winter and during migration, they inhabit broad, coastal beaches with light-colored sand. They can also be found on gravelly and rocky beaches and mudflats, and on top of kelp beds. In the fall, adults dominate the optimal habitats, and juveniles take the remaining spots.

Behavior

Sanderlings flock, and members of different flocks interchange freely. The quintessential surf-dodger, the Sanderling is most recognized for its behavior of running down to the water's edge with an outgoing wave, and racing back up the beach to avoid the next incoming wave. Dunlins and Western Sandpipers also do this, so this behavior is not diagnostic. They feed by probing, and leave bands of holes along a beach where they have stuck their beaks into the sand probing for food. They also feed in tire tracks. When roosting, they usually stand on one leg, and if disturbed, they will hop away from the disturbance on one leg.

Diet

Sanderlings dine on a variety of aquatic invertebrates and sometimes carrion. One study identified young razor clams as a major source of food on the Washington coast.

Nesting

Sanderlings nest on the dry, northern tundra, often close to lakes or ponds. The nest is on the ground, often on an elevated spot out in the open. The nest is a shallow scrape lined with leaves. The female generally lays two clutches, and either two males, or one male and the female herself, each incubate a clutch of four eggs. If the female has two males incubating the eggs, she will depart. If she is incubating a clutch, she will stay with the young, which hatch after 24 to 31 days, until they fledge at about 17 days. Males also stay with the young, which leave the nest and can feed themselves immediately after hatching.

Migration Status

This is the only shorebird species in which an individual has been recorded on both coasts of North America during migration, indicating that the migration path of the Sanderling is a wide oval. Migrating birds make long, non-stop flights between traditional stopover points. They have one of the largest latitudinal winter ranges of any shorebird. Adults leave the breeding grounds in July through mid-August, with juveniles following one month later. Sanderlings of Greenland and Siberia winter throughout coastal Africa and across the southern coast of Eurasia. The Canadian population winters along both coasts of South America as far south as Tierra del Fuego.

Conservation Status

The Canadian Wildlife Service estimates the worldwide population of Sanderlings at 643,000 birds, with 300,000 breeding in North America and the remainder across Eurasia. Although the Sanderling is one of our most common sandpipers and has a worldwide distribution, it has experienced serious declines, as much as 80% of the population since the early 1970s. Sanderlings rely heavily on a small number of staging areas during migration, and destruction of these areas can seriously affect the population. Declines are probably due to disturbance on feeding areas during migration. The populations on the Pacific Coast fluctuate, but Christmas Bird Count data suggest that the wintering population in the Northwest has actually increased in recent years.

When and Where to Find in Washington

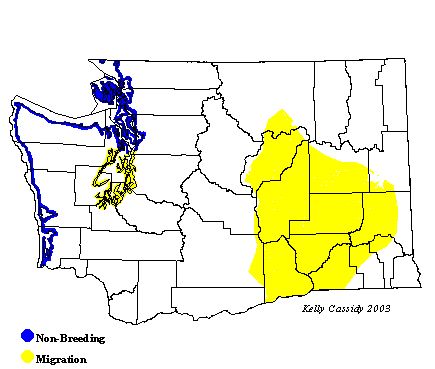

Sanderlings are common migrants and wintering birds along Washington's outer coastline. In fact, the highest densities of Sanderlings on the Pacific Coast are around the mouth of the Columbia River in southwest Washington and northwest Oregon. Birds start returning to Washington in early July, but are uncommon until mid-July. After that, they are common until the following June. The pattern is confounded by the fact that some first-year birds summer on the wintering grounds, so small numbers of Sanderlings are present on the coast year round. Summering birds are often found at Leadbetter Point. In the protected waters of Puget Sound, Sanderlings are uncommon but present, year round, sometimes as far south as Olympia. In the winter these birds are likely to be juveniles, as adults more commonly winter on the outer coast. In eastern Washington, Sanderlings are a rare but regular migrant. They are more common there during fall migration than spring.

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | C | C | C | C | C | U | F | C | C | C | C | C |

| Puget Trough | C | C | C | F | U | R | U | C | C | C | C | |

| North Cascades | ||||||||||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | ||||||||||||

| Okanogan | ||||||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | R | U | R |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius

Spotted SandpiperActitis macularius Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria

Solitary SandpiperTringa solitaria Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes

Gray-tailed TattlerTringa brevipes Wandering TattlerTringa incana

Wandering TattlerTringa incana Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca

Greater YellowlegsTringa melanoleuca WilletTringa semipalmata

WilletTringa semipalmata Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes

Lesser YellowlegsTringa flavipes Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda

Upland SandpiperBartramia longicauda Little CurlewNumenius minutus

Little CurlewNumenius minutus WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus

WhimbrelNumenius phaeopus Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis

Bristle-thighed CurlewNumenius tahitiensis Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus

Long-billed CurlewNumenius americanus Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica

Hudsonian GodwitLimosa haemastica Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica

Bar-tailed GodwitLimosa lapponica Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa

Marbled GodwitLimosa fedoa Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres

Ruddy TurnstoneArenaria interpres Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala

Black TurnstoneArenaria melanocephala SurfbirdAphriza virgata

SurfbirdAphriza virgata Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris

Great KnotCalidris tenuirostris Red KnotCalidris canutus

Red KnotCalidris canutus SanderlingCalidris alba

SanderlingCalidris alba Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla

Semipalmated SandpiperCalidris pusilla Western SandpiperCalidris mauri

Western SandpiperCalidris mauri Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis

Red-necked StintCalidris ruficollis Little StintCalidris minuta

Little StintCalidris minuta Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii

Temminck's StintCalidris temminckii Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla

Least SandpiperCalidris minutilla White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis

White-rumped SandpiperCalidris fuscicollis Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii

Baird's SandpiperCalidris bairdii Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos

Pectoral SandpiperCalidris melanotos Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata

Sharp-tailed SandpiperCalidris acuminata Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis

Rock SandpiperCalidris ptilocnemis DunlinCalidris alpina

DunlinCalidris alpina Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea

Curlew SandpiperCalidris ferruginea Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus

Stilt SandpiperCalidris himantopus Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis

Buff-breasted SandpiperTryngites subruficollis RuffPhilomachus pugnax

RuffPhilomachus pugnax Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus

Short-billed DowitcherLimnodromus griseus Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus

Long-billed DowitcherLimnodromus scolopaceus Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus

Jack SnipeLymnocryptes minimus Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata

Wilson's SnipeGallinago delicata Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor

Wilson's PhalaropePhalaropus tricolor Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus

Red-necked PhalaropePhalaropus lobatus Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius

Red PhalaropePhalaropus fulicarius